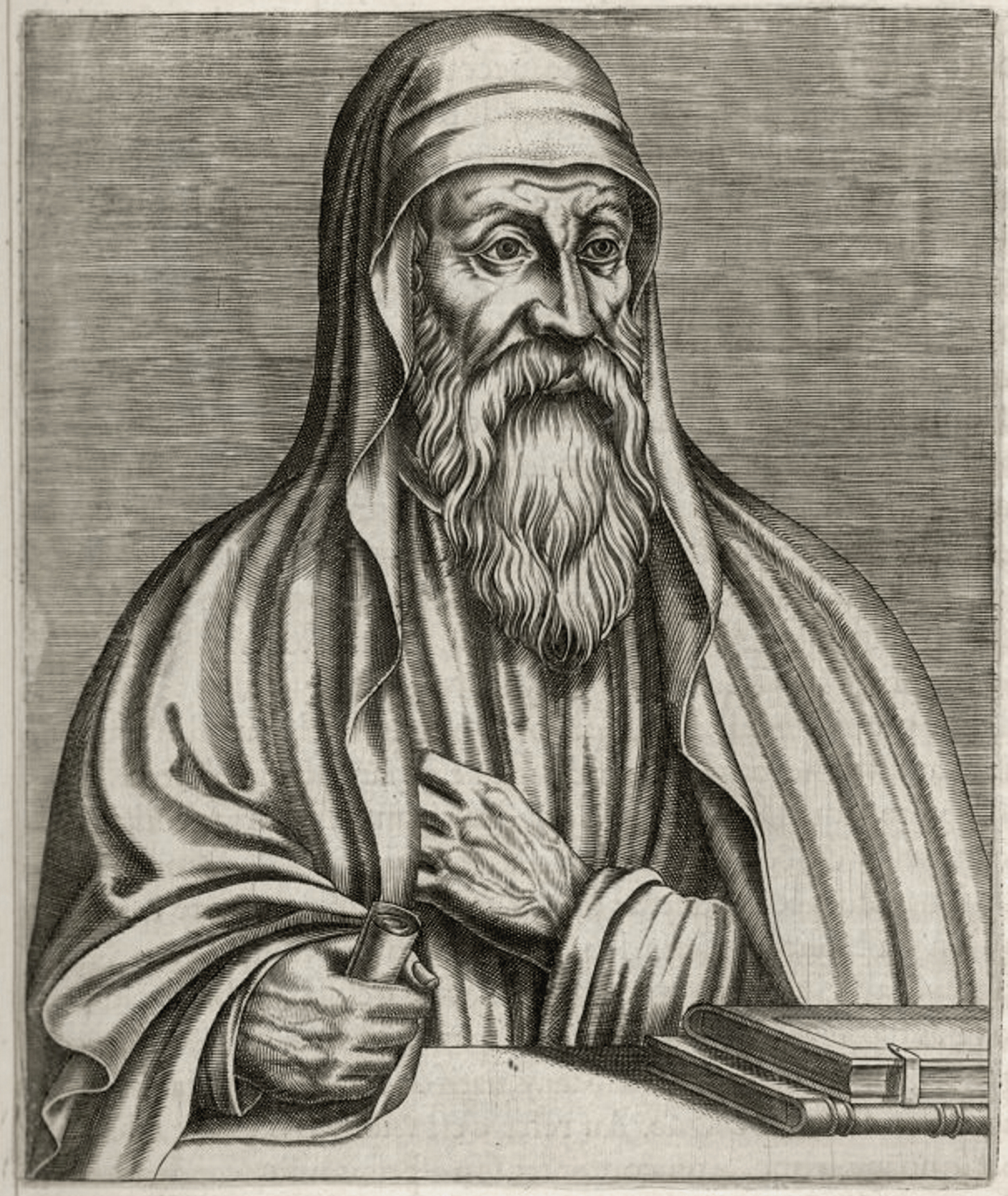

While honest skepticism about the resurrection of Jesus is understandable, practically everyone accepts the crucifixion of Jesus as a historical fact. The consensus is that Roman soldiers in 1st Century Jerusalem executed a Galilean rabbi named Jesus. The biblical accounts of his death vary somewhat in the details, of course, yet they are similar enough that there is no question that they are describing the same event. Also, we are fortunate to have a solid, non-biblical reference to Jesus’ execution provided by the 1st Century Roman historian, Tacitus (pictured):

“Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilate, and the pernicious superstition was checked for a moment, only to break out once more, not merely in Judea, the home of the disease, but in the capitol itself [i.e., Rome] where all things horrible or shameful in the world collect and find a vogue.” (Tacitus, Annales, XV:44) (italics mine)

Not only is Tacitus a 1st Century, non-biblical witness (though not an eyewitness) to Jesus, his death, and those who believed in “the name,” but he is a hostile witness. He calls Christianity a “disease,” a “pernicious superstition,” “horrible” and “shameful.” Tacitus was hardly a Christian supporter or sympathizer, lending more credibility to his record.

In my view, this quote from Tacitus confirms three things for this book. One, it is a historical fact that Jesus (Christus) was executed in Judea by Pontius Pilate during the reign of Tiberius. Two, Jesus' death only for a short time stopped the Christian movement. And three, Tacitus considered Christianity a "pernicious superstition.”

The third one interests me. Why did Tacitus classify Christianity as a superstition? There is nothing superstitious surrounding Jesus' death, which Tacitus verifies. (Christians and non-Christians acknowledge Jesus’ crucifixion as a historical occurrence today largely owing to this quote from Tacitus.) By “pernicious superstition” I wonder if Tacitus might have been referring to the central Christian belief that Jesus rose from the dead. Admittedly, from Tacitus’ time to today, many consider belief in Jesus’ resurrection to be mere superstition. Even those of us who call ourselves Christians must admit, if we are honest, that accepting without question that Jesus was resurrected is impossible.

|

| Joseph Campbell |

Like many Christians, I have toyed with the idea that the resurrection stories might be symbolic. Maybe the resurrection was a literary metaphor for the way in which Jesus' message lived on in the memory and work of his disciples. (World mythology expert, the late Joseph Campbell, pictured, would be proud.) And I have asked myself, Why can't I simply accept that the Bible says that he arose, so therefore he arose? I could have saved myself a lot of work! Yet I cherish the opportunity to move beyond blind acceptance. Besides, skeptics must doubt and question. It’s what we do.

I want it to be clear that what I’m writing here is not an effort at evangelizing, as if a well reasoned analysis of the resurrection might compel someone to become a Christian. My motive in writing about the resurrection is not to change hearts or save souls, but simply to engage the scriptures in a serious way. My belief and my unbelief compel me to examine thoroughly the available evidence.

Of course some may argue that I am trying to prove the resurrection, and that faith requires no proof. I agree that faith, by definition, does not need proof. But I don’t believe in checking my brain at the door either! For me to fail to explore this issue historically would be intellectual suicide. Besides, it is not proof I’m seeking. I don’t require certainty. What I want to do is explore the evidence, keeping in mind two things: One, it is not likely that I will prove anything once-and-for-all to myself or anyone else by this effort. And two, I believe deeply that my investigation of the resurrection of Jesus will have some benefit to somebody, if only me.

The guiding question in this section will be this:

If Jesus did not rise from the dead, then how can _____ be explained?

This section is an exploration of biblical evidence supporting the resurrection of Jesus as an actual event no less historical than his crucifixion. I will explore ten points at which I feel it is difficult to explain away his resurrection from the dead. You will glimpse the state of mind of Jesus’ followers before, during, and after the events of Holy Week. Critical to this section is an analysis of the effect these events had on Jesus' followers, and the sudden resuscitation of their crushed campaign.

1. The disciples in all of the biblical accounts believed that they had actually seen Jesus after his death. Their claim to have had firsthand experiences of the risen Jesus sounds self-explanatory, but it should be stated first nonetheless. Matthew, Luke, and John (and Mark’s longer ending, if you wish to include it) all record appearance stories: the disciples see him, walk with him, touch him, eat with him, and talk with him. Could they have been lying? Yes, but if so, why? Could they have been mistaken? Yes, but if so, how? These questions anticipate upcoming points. The point here is that the gospels claim that the disciples said they saw him. There is no record of them ever recanting.

2. To whom did the risen Lord appear? By and large, he appeared to believers only. Matthew, Luke, John, Acts, and 1 Corinthians give us the recorded experiences the disciples had of the risen Christ. I’ll also include the witness of Mark 16:9-20 below, though this longer ending of Mark is usually footnoted as a later addition. Here are the witnesses:

1-Matthew 28:1-10 --- to Mary Magdalene and the other Mary as they ran from the tomb

2-Matthew 28:16-20 --- to the eleven on a mountain in Galilee

1-Mark 16:9-11 --- to Mary Magdalene

2-Mark 16:12-13 --- to two disciples walking into the country

3-Mark 16:14-20 --- to the eleven while at table

1-Luke 24:1-32 --- to Cleopas and another disciple walking to Emmaus

2-Luke 24:33-35 --- to Simon Peter

3-Luke 24:36-53 --- to the eleven plus companions

1-John 20:11-18 --- to Mary Magdalene outside the tomb

2-John 20:19-23 --- to disciples minus Thomas

3-John 20:24-29 --- to disciples including Thomas a week later

4-John 21 --- to seven disciples on the shore of the Sea of Galilee

1-Acts 1:3-5 --- to disciples, teaching during forty days (Passover-Pentecost)

2-Acts 1:6-11 --- to disciples who witness his ascension

(3-Acts 9:1-9 --- to Saul/Paul on the road to Damascus—not an appearance like others)

First Corinthians 15:3-11 - the tradition handed to Paul says the risen Christ appeared:

1 --- to Cephas (Peter)

2 --- then to the twelve (at first eleven)

3 --- then to more than five hundred believers at one time

4 --- then to James (Jesus' brother and eventual leader of the church in Jerusalem)

5 --- then to all apostles

6 --- then to Saul/Paul last

This is a complete list of Jesus’ resurrection appearances in the Bible. In just thirty minutes you should be able to look up and read these verses. These are the only stories that the early church deemed accurate and authoritative concerning Jesus’ resurrection appearances.

A crucial thing to me about these stories is that with only two exceptions, Jesus only appeared to believers. He appeared to those who previously followed him. You may be wondering why. Wouldn’t it have been better if Jesus had appeared to the High Priest Caiaphas also, and to the whole Jewish Sanhedrin? Shouldn’t he have appeared to Pilate and Herod? Why show himself to believers only when proof of his resurrection could have been secured forever by appearing widely to rulers and record keepers? Why didn’t he appear to the Emperor in Rome?

The way Jesus did it left open two complaints. One, by appearing only to believers, it can be argued that the believers could have made it all up. And two, it only makes logical sense that if Jesus really rose from the grave that he would have wanted to appear to objective non-believers as stronger proof. These two complaints are legitimate.

My first answer to these complaints is based on the character of Jesus displayed throughout the Gospels. He’s never showy. Point in fact, Jesus almost always healed people in private. Here are three examples from Mark:

- Mark 5:37-42 He allowed no one to follow him except Peter, James, and John, the brother of James. 38 When they came to the house of the leader of the synagogue, he saw a commotion, people weeping and wailing loudly. 39 When he had entered, he said to them, "Why do you make a commotion and weep? The child is not dead but sleeping." 40 And they laughed at him. Then he put them all outside, and took the child's father and mother and those who were with him, and went in where the child was. 41 He took her by the hand and said to her, "Talitha cum," which means, "Little girl, get up!" 42 And immediately the girl got up and began to walk about (she was twelve years of age).

- Mark 7:33-36 He took him aside in private, away from the crowd, and put his fingers into his ears, and he spat and touched his tongue. 34 Then looking up to heaven, he sighed and said to him, "Ephphatha," that is, "Be opened." 35 And immediately his ears were opened, his tongue was released, and he spoke plainly.

- Mark 8:22-25 They came to Bethsaida. Some people brought a blind man to him and begged him to touch him. 23 He took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the village; and when he had put saliva on his eyes and laid his hands on him, he asked him, "Can you see anything?" 24 And the man1 looked up and said, "I can see people, but they look like trees, walking." 25 Then Jesus1 laid his hands on his eyes again; and he looked intently and his sight was restored, and he saw everything clearly.

He wasn’t there to prove he could heal. He never spotlighted himself. His last miracle, the raising of Lazarus from the dead, wasn’t done privately, true, but he said he knew that this miracle would result in his arrest and death, which was his intent. Only at the end did he make a public show of a conspicuous sign of power, and it cost him his life. Otherwise, he typically healed people privately or inconspicuously. That was his modus operandi.

My question is: Why would his character change if he were raised from the dead? The risen Jesus appeared privately to people who knew and loved him already, and to them only. He was not interested in coercing faith with proofs in his earthly ministry. Why would he do differently in his resurrection? He didn’t pop in on Pilate because he refused to force anyone’s faith with showy demonstrations. By appearing risen to believers only, he confirmed the faith in him that they already had. The rest of us would just have to believe their witness or not. The believers’ witness to his resurrection, for Jesus, seems to have been enough.

There are two exceptions to this. Jesus’ brother James and a Pharisee named Saul (later nicknamed the Apostle Paul). Neither of these men believed in Jesus during his ministry. But as it turned out later, Brother James became the first leader of the church in Jerusalem, and the Apostle Paul became the primary missionary to the Roman world. Jesus apparently showed himself to James and Paul not to prove anything to the world, but because he needed them—their objectivity and their talents—to spread the gospel of forgiveness of sins to Jews and to Gentiles in Israel and beyond.

My second answer: John’s gospel states clearly that the faith of those who believe only because of miracles is incomplete and not to be trusted:

- John 2:23-25 When he was in Jerusalem during the Passover festival, many believed in his name because they saw the signs that he was doing. 24 But Jesus on his part would not entrust himself to them, because he knew all people 25 and needed no one to testify about anyone; for he himself knew what was in everyone.

This is a very telling verse. Not only did Jesus perform miracles privately and insist on their silence about them, but he also didn’t trust people whose faith was built on miracles. Why? Because he knew human nature. We’re sensation addicts. We don’t want faith based on trusting a person and his message. We want signs and wonders. We’d rather be wowed. Entertainment and sensationalism sell precisely because of this, as televangelist “faith healers” still demonstrate today. Jesus didn’t trust people who hung around hoping to spy something flashy. John records the risen Jesus saying:

- John 20:29b “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.”

Because faith is a matter of believing when you haven’t seen, the only witnesses to the resurrection were Jesus’ friends and two unlikely characters: James, Jesus’ unbelieving brother, and Paul, a persecutor of Christians. To me it is just like Jesus to put together women (whose witness is not permissible in a Jewish court of law), average laymen (his disciples were fishermen, tax collectors, and revolutionaries), his own brother (who rejected him and thought him insane), and a fanatical Pharisee (a Jewish scholar who hated and hunted Christians). These were Jesus’ handpicked witnesses to the resurrection! Either you believe these witnesses or none.

And my third answer: Jesus even downplays the resurrection itself as a flashy sign. When Mary Magdalene first sees the risen Lord, she doesn’t recognize him. But when Jesus says her name, she recognizes him and tries to hold him. But he stops her and says:

- NLT John 20:17 "Don't cling to me . . . for I haven't yet ascended to the Father. But go find my brothers and tell them that I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God."

Apparently even the resurrection itself is not to be made into a sign that proves your faith. Don’t cling to me, he said. The resurrection is not the point. Who he is as the Father’s Son is the point. His return to his Father’s side is the point. His union with his Father is the point and the message. The resurrection, like all signs and miracles, must be seen as a mere pointer to the central theme of who Jesus says he is.

Faith is not decisional but relational. Faith isn’t the substance of miracles and proofs, but belief in who Jesus is in the absence of miracles and proofs. Don’t cling to his resurrection, miraculous though it may be, says John. Instead let your faith cling to who he is in oneness with his Father. For in his oneness with his Father, the whole human race is made one with his Father. That’s the good news that Jesus wants told. That’s the good news to which the resurrection points.

John says that’s the message. God has forgiven the world that rejected him. The resurrection is intended as confirmation of that truth. The resurrection points beyond itself to the Father’s amazing grace to the whole human race in the crucified Christ. The resurrection vindicates the cross as the way God’s mercy works. Not even our killing of his Son can destroy the love of God for us. On the contrary, that killing saved the world. It’s not flashy. But God’s mysterious humility is the core of his character. It’s not about showboating like they do on the Televangelism Broadcasting Network.

Besides, Jesus apparently didn’t rise from the dead to prove anything in the first place. At the end of one of Jesus’ parables about greed there is this wicked little twist of the knife:

- Luke 16:31 'If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.'

It might at first seem that Jesus’ “failure” to appear to objective observers and VIPs is an argument against the historicity of his resurrection. Yet I see his appearance to disciples only (with two notorious exceptions) as perfectly in keeping with the character of the pre-crucifixion Jesus. He never did anything ostentatious for proof. He invited faith to be freely chosen without proof. Ironic, isn’t it, that proof, rather than awakening faith, puts faith to sleep.

Is it possible that the disciples could have made it all up? Yes. Isn’t it logical that if Jesus wanted to prove his resurrection, that he would have appeared to someone in power? Yes. Yet I don’t think it’s likely that we’re dealing with a vast conspiracy, and I don’t think proving anything was ever on Jesus’ to-do-list.

3. What was the disciples’ initial response to the resurrection? They didn’t believe the news. They didn’t even believe it when he stood right there in front of them. This argues for the resurrection.

At first it seems strange that the disciples were startled by the reports of Jesus' resurrection. After all, Jesus himself told them repeatedly that he would rise (Mark 8:31, 9:31, 10:33-34). Yet if their understanding of resurrection was similar to that of the Pharisaic Judaism of their day, then they understood resurrection as something to come in the last days, as Daniel prophesied, marking the end of history. (See John 11:23-24) What the disciples could not fathom apparently was that the resurrection Jesus spoke of could occur within history. Thus their surprise. (Int. Dic., Res. in the NT, p. 45)

I think that the Gospels’ honest descriptions of the disciples’ unbelieving responses to Jesus’ resurrection are telling. No Gospel says they handled it well.

The Gospel of Mark is probably the oldest Gospel, and it ends most unusually. While there are three tacked on endings to Mark that are as close as the footnotes after Mark 16:8, the oldest and most reliable copies of Mark in existence today end at Mark 16:8 (marking the longer endings as later scribal attempts to “round off” Mark’s blunt ending). Can you believe that Mark’s Gospel ends like this?

- Mark 16:5-8 As [the women] entered the tomb, they saw a young man, dressed in a white robe, sitting on the right side; and they were alarmed. 6 But he said to them, "Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him. 7 But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you." 8 So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.

Mark’s Gospel ends with the women running away scared and silent. An odd ending for sure, if a Gospel is supposed to prove Jesus rose. But what if that wasn’t Mark’s purpose? What if instead Mark ends this way to avoid proofs so as to arouse faith?

The Gospel of Matthew, though it does seek to prove the resurrection of Jesus, bluntly claims that some of the disciples didn’t believe even though they had seen him.

- Matthew 28:17 When they saw him, they worshiped him; but some doubted.

Again, apparently seeing isn’t believing.

The Gospel of Luke doubles up on the doubt. The men don’t believe the women’s claim that they saw him risen from the dead, probably not only because the news of his resurrection is unbelievable in and of itself, but also because women’s testimony was not acceptable in Jewish courts and therefore unacceptable generally, and because if Jesus were to appear to anyone, surely (they must have thought) it would be to the men from Galilee that Jesus handpicked.

- Luke 24:10-11 Now it was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women with them who told this to the apostles. 11 But these words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them.

Then Luke, poetic to a fault, tells us that when Jesus then appeared to the men, they were terrified and misunderstood what they saw. Then even after being comforted and corrected by Jesus, their joy was still mixed with unbelief.

- ESV Luke 24:37-43 But they were startled and frightened and thought they saw a spirit. 38 And he said to them, "Why are you troubled, and why do doubts arise in your hearts? 39 See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself. Touch me, and see. For a spirit does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have." 40 And when he had said this, he showed them his hands and his feet. 41 And while they still disbelieved for joy and were marveling, he said to them, "Have you anything here to eat?" 42 They gave him a piece of broiled fish, 43 and he took it and ate before them. (italics mine)

Luke puts it so well, doesn’t he? They disbelieved for joy.

The Gospel of John emphasizes doubt arguably more than the other Gospels by giving to us the story of Thomas’ absence at Jesus’ first appearance to the eleven. Thomas declares:

- John 20:25 "Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe."

The next Sunday, Jesus appeared to the eleven, this time with Thomas present. Rather than chastising Thomas for his doubt, Jesus gave him an open invitation and a blessing to all the Doubting Thomases of the world.

- John 20:27-29 "Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe." 28 Thomas answered him, "My Lord and my God!" 29 Jesus said to him, "Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe."

The four Gospel writers could have cleaned up the mess. Instead they admit—no, they insist—that the disciples responded less than faithfully to Jesus’ resurrection. The early Church as well had every opportunity to remove such doubting from the Gospel records. But they didn’t. Why? Perhaps because it was true. They doubted.

To one way of looking at this, the doubts of the disciples should confirm our own doubts about someone in human history rising immortal from the dead. They didn’t believe it so why should we? Yet from an opposite angle, how could any human being respond any other way but doubtfully when presented with something as shocking and unexpected as Jesus’ resurrection? Does the Gospels’ honesty about the disciples’ doubts strengthen the biblical account’s plausibility?

4. The timing of the disciples’ proclamation of the resurrection argues for the historicity of the event. They were claiming Jesus rose from the dead in the Jerusalem temple mere weeks after the crucifixion. The Book of Acts, written by the same author of the Gospel of Luke, records the events some forty days following Jesus’ death, resurrection, many appearances, and ascension.

- Acts 4:1-2 While Peter and John were speaking to the people, the priests, the captain of the temple, and the Sadducees came to them, 2 much annoyed because they were teaching the people and proclaiming that in Jesus there is the resurrection of the dead. (italics mine)

The disciples were quick to get organized and spread the word that Jesus arose from the dead. Does that make you suspicious that they plotted doing that very thing in advance? It wasn’t months or years later that they began proclaiming to the world that Jesus arose. It was almost immediately. It was the most dangerous time to do so. They were arrested for the first time for their bold move in Acts 4, but it would not be the last. Suspicious? Or is their quick proclamation of Jesus’ resurrection the very thing you wouldn’t have expected so soon after his tragic execution right there in Jerusalem? That leads us to the next argument.

5. The disciples were transformed almost overnight from a band of scattered fugitives who denied and abandoned their executed leader, into bold, loyal, public proclaimers that Jesus was the Messiah and that he was raised from the dead. How could that happen?

The disciples' concern for Jesus' safety and their own began earlier in the Gospel accounts when Herod Antipas (pictured on coin) beheaded John the Baptist. Their concern grew when Jesus told them he planned to go to Jerusalem. The Jewish authorities pressed Jesus harder as time passed, and they tried to arrest him with the intent to kill him. The events I’m about to outline show that the disciples had good reason for being afraid. The Gospels show that the twelve performed poorly under the strain of these events.

Herod Antipas' extremely long reign, 4 B.C. - A.D. 39, suggests that he was adept at both preventing and crushing uprisings in his territories of Galilee and Perea. Likely he became concerned about Jesus' ministry in Galilee because of the crowds drawn by his teaching and healing. Crowds can quickly become mobs. Herod would have wanted to prevent that, as those who monitored Jesus' activities for Herod would have known well. (Matthew 22:16; Mark 3:6, 12:13)

When Jesus heard that Herod had beheaded John, he spoke against Herod in or near Bethsaida. He warned his disciples, "Watch out -- beware the yeast of the Pharisees and the yeast of Herod." To speak against the King of Galilee while in Galilee was dangerous to say the least.

Jesus led his disciples to the region of Caesarea Philippi, thus escaping Herod’s reach for a time while he pondered his plan to reenter Jerusalem to die. There, for the first time, Jesus explained his plan to go to Jerusalem, and that he expected to be killed there. Peter was probably speaking for all the disciples when he protested against Jesus' plan. Peter took Jesus aside and scolded him saying, "God forbid it, Lord! This must never happen to you." (Matthew 16:22) But Jesus had made up his mind, for Luke wrote he had set his face to go. (9:51) So very determined was he to return to Jerusalem to confront the Jewish authorities in the temple, that Mark says Jesus began striding ahead of the disciples on the road. This truly terrified them.

- Mark 10:32 They were on the road, going up to Jerusalem, and Jesus was walking ahead of them; they were amazed, and those who followed were afraid.

John's Gospel records that Jesus' disciples were very concerned about the Jews (the Judean authorities). There were attempts to arrest Jesus in the temple, but each time he managed to escape. When Jesus told his disciples he planned to go to Jerusalem again, they tried to restrain him.

- John 11:8 "Rabbi, the Jews (Judean authorities) were just now trying to stone you, and are you going there again?"

Once more the disciples were unsuccessful in curbing their master. Thomas said, either sarcastically or bravely, "Let us also go, that we may die with him." (John 11:16)

When Jesus reached Jerusalem, some Pharisees who believed in him warned him that Herod was looking to kill him. Again he spoke against Herod saying,

- Luke 13:32-33 “Go and tell that fox for me, ‘Listen, I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work. 33 Yet today, tomorrow, and the next day I must be on my way, because it is impossible for a prophet to be killed outside of Jerusalem."

The disciples' excitement over Jesus' "triumphal entry to Jerusalem" on a donkey must have been tempered by their concern for Jesus' safety. They were aware that both Roman and Jewish authorities were watching them. The large crowds offered them protection, but the danger in these actions was real. Again he was warned by friendly Pharisees in the crowd, "Teacher, order your disciples to stop." (Luke 19:39) They were concerned about his drawing so much attention, as were the twelve themselves no doubt.

- Matthew 21:9-10 The crowds that went ahead of him and that followed were shouting, "Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest heaven!" 10 When he entered Jerusalem, the whole city was in turmoil,

Jesus was aware of the likelihood of trouble, and he tried to prepare his disciples, probably that very same day:

- Luke 22:36 ". . . [N]ow the one who has a purse must take it, and likewise a bag. And the one who has no sword must sell his cloak and buy one."

The disciples' response is surprising.

They said, "Lord, look, here are two swords." (Luke 22:38a)

How did Jesus respond?

He replied, "It is enough." (Luke 22:38b)

Without telling Jesus, the disciples had already armed themselves! This is strong evidence that they were aware of the danger involved in being where they were and doing what they were doing. The swords suggest that they were anxious and prepared for trouble.

The disciples had retired that evening to their customary place on the Mount of Olives. Judas, one of Jesus' trusted twelve, divulged his nighttime whereabouts to the authorities and led them there. Luke 22:45 describes the disciples as having fallen asleep there "because of grief." This statement confirms the depth of their anxiety. They were exhausted.

The disciples were awakened and surprised by an approaching crowd.

- John 18:3 So Judas brought a detachment of soldiers together with police from the chief priests and the Pharisees, and they came there with lanterns and torches and weapons.

The disciples asked Jesus for permission to fight.

- Luke 22:49 When those who were around him saw what was coming, they asked, “Lord, should we strike with the sword?”

Before he could answer, one of the disciples (John's Gospel says the swordsman was Peter) took a swipe at the high priest's slave, slightly wounding him. Jesus said, "No more of this!" The authorities laid hands on Jesus, and as they did this, his disciples escaped into the darkness.

- Mark 14:50 All of them deserted him and fled.

After their escape, only Peter and John followed Jesus at a distance. The crowd came to the high priest's home (probably Annas, not Caiaphas, and it was probably a privy council, not the full Sanhedrin which would have met the next day. See Who Was Jesus?, Boers). (John 18:13 & 24) The crowd went inside while John and Peter watched and overheard from the house’s central courtyard.

Peter joined some people who were warming themselves by a charcoal fire. It was here that one of the high priest's servant-girls recognized Peter. Three times she and other bystanders accused him of being one of Jesus’ Galilean followers. He swore repeatedly that they were wrong. When he realized what he had done, that he had lied to save himself, that he had denied his Lord, he ran away weeping bitterly. Only one disciple, reportedly "the beloved disciple" whom we may assume is John, mustered the courage to attend Jesus’ trials and execution. The rest scattered and hid.

The disciples had every reason to scatter and hide. Who could they trust? One of Jesus' own twelve full-time disciples had led the authorities to him. The others had put up feeble resistance when the authorities came to arrest him. Only two had swords. Only one was used and not very well. They all deserted him and fled. One denied he knew Jesus three times under questioning and fled (again). The one who turned him in committed suicide. Intense shame and fear sent the rest scattering for cover.

The purpose of this section is to show the intense pressure under which the disciples were operating. Their performance, though often criticized as cowardly, is to me quite understandable. Their lives were in danger. Who knows how one might act under such strain until it happens? So, though I am sympathetic to the plight of Jesus' twelve, it would be ridiculously optimistic (and unbiblical) for me to hold that as a group they handled things well. They better than anyone must have been shamefully aware that when it counted they were weak. How they actually felt that day or the next is a matter of conjecture. Nevertheless, Peter running off into the dark alone and in tears is a fair characterization, I believe, of the experience of each of the eleven.

The question at the heart of this section is: How could a defeated, frightened, scattered, guilt-ridden band of disciples have been so instantaneously reunited, reinvigorated, and filled with joyous purpose and public fearlessness?

Some joint experience is necessary. How else can one explain the sudden resuscitation of a failed, crushed movement? And what event could account for a band of frightened, scattered fugitives devastated by their own failure, grief, and despair being so quickly regrouped, working together, and making bold public stances everywhere, including in the Jerusalem temple (see Acts 4 and 5) before the very authorities who cruelly disposed of Jesus?

Supposedly Jesus' followers disbursed upon the death of their leader, and that was the end of their movement. As far as the Romans were concerned, they had crucified another Jew guilty of sedition, and his followers had fled like the followers of all executed insurrectionist leaders. The Jewish authorities believed they had succeeded in saving their offices. An uprising had been prevented, they believed. So the Jews (the Judean authorities) had accomplished what they plotted to do, and they had every reason to believe that the whole matter was closed, and their work complete. The Roman historian Tacitus, remember, sounded frustrated that such a "pernicious superstition," i.e., Christianity, could, against all expectation, flourish again not long after the death of its founder.

In Acts 5, a Pharisee named Gamaliel cautions his fellow Jewish leaders on how to deal with Jesus' surprising followers, whom they arrested a third time for preaching that Jesus rose from the dead:

- "Fellow Israelites, consider carefully what you propose to do with these men. Thadeus rose up, claiming to be somebody, and a number of men, about four hundred, joined him; but he was killed, and all who followed him were disbursed and disappeared. . . . Judas the Galilean rose up . . . and got people to follow him; he also perished, and all who followed him were scattered. So in the present case (that of the followers of the crucified Jesus of Nazareth), I tell you, keep away from these men and let them alone; because if this plan or this undertaking is of human origin, it will fail; but if it is of God, you will not be able to overthrow them -- in that case you may even be found fighting against God!" (Acts 5:35-39)

Gamaliel argued against killing Jesus' followers, perhaps because he was struck by their unprecedented continuing faith in their fallen leader. Surely no one would have predicted that these disciples would emerge from hiding to proclaim publicly Jesus' messiahship and his resurrection from the dead. If Gamaliel and company were not surprised by this turn of events, they should have been. Acts only records that they were enraged, and that without Gamaliel's intervention, they would have killed the twelve (Acts 5:33-34), perhaps on the spot.

Something brought these disciples back together. It may be possible that they gathered Saturday or Sunday in grief and fear, as Zeitlin believes, aware that they had failed to act with honor and courage (p. 165). So perhaps they assembled to console one another. Or maybe they resided together for mutual protection, laying low for a while to make sure the authorities were not searching for them, as it is portrayed in Hollywood movies. These are possibilities. But it is more probable, and is strongly implied by both Luke and John, that they were called together Sunday evening by reports that Jesus was appearing to some of them. In spite of the danger, and in utter perplexity (and perhaps hope), they risked calling one another together to discuss the claims that Mary of Magdala, Peter himself, and others, had been visited by their crucified Lord.

What I’m suggesting is that they wouldn’t have met together that Sunday evening and perhaps ever again unless something momentous happened to force them to risk doing so. The risen Jesus appearing to some of them might have been the “something momentous.”

John 20:19 mentions a particular house where the disciples met Sunday. John 20:26 records they met again in the same house a week later. This Gospel is conveying that they were not residing together, but the disciples were calling meetings in a safe-house -- "for fear of the Jews" -- at specified times.

Luke 24:33 describes how two disciples discovered when and where the eleven (plus other companions) were meeting. The way Luke puts it, the two found them gathered together.

- Luke 24:33 That same hour they got up and returned to Jerusalem; and they found the eleven and their companions gathered together. (italics mine)

To include this detail of them being found together suggests that when Cleopas and his travel companion rushed back to Jerusalem from Emmaus that they were not expecting them to be meeting. These two disciples from Emmaus were a part of the scattering that took place after the crucifixion. By Easter Sunday noon, no gathering had taken place yet, and no meeting had yet been called. One might even hear in this description by Luke an element of surprise. “and (surprise) they found the eleven and their companions gathered together.”

Expecting to have to reach them individually, given that all of them had scattered about, these two returning from Emmaus—the evening of that same Easter Sunday—discovered that all of them were in the same place under cover of darkness behind locked doors. The two from Emmaus were unaware that a meeting had been called or why. They came back to find Peter and the others to tell them that they had actually seen and talked with Jesus. Upon arriving in Jerusalem (guardedly), they likely asked (cautiously) where any of the disciples might be. But they were surprised to find them having a meeting. If the disciples had stayed together continuously Friday night through Sunday, why would it have been necessary for Luke to specifically write that they were found gathered? Similarly, if they had been together continuously Friday night through Sunday, why would John have clarified that when they met there they locked the door?

- John 20:19 When it was evening on that day, the first day of the week (Easter Sunday), and the doors of the house where the disciples had met were locked for fear of the Jews (the Judean authorities) . . .

If the disciples had been together continuously from the Friday of Jesus’ crucifixion onward, why would it have been necessary for John to point out that a week later they met again behind locked doors in the same house?

- John 20:26 A week later his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were shut, Jesus came and stood among them and said, "Peace be with you."

Clearly the disciples were not cohabiting, but started calling secret meetings beginning the Sunday evening after the crucifixion. One such meeting followed a week later.

Why is it important to substantiate that they were not together continuously? Because if they were not together continuously, it must be concluded that they began calling meetings together very soon after Jesus' death. If they began calling meetings, there must have been a crucial reason to do so beyond consoling one another. Frankly, what consolation could anyone have given? Could anyone say to Peter, "Though you ran to save your own neck--twice, and though you denied you knew Jesus--thrice, you're still a swell guy and everything's gonna be okay?" Shamefulness alone, danger notwithstanding, would have prevented them from regrouping. They all failed him. Who would want to show their face after such extreme disgrace?

When other messianic leaders were slain in Israel under Roman rule, followers did not regroup. It was futile, not to mention dangerous, to regroup when the leader was executed by Rome. What would be the point? So why in this case did the disciples of Jesus risk calling a meeting? The only reason the Gospels give is that they gathered to deal with strange reports from women, Peter, and other usually sane and reliable disciples, that Jesus -- their crucified leader, the one they abandoned to be arrested and killed -- was paying them visits.

Could the disciples have gotten back together immediately after Jesus crucifixion to plan a vast conspiracy? To me, the explanation that the disciples stole his body and spread an out-and-out lie about his resurrection openly, daily, continually, even in the Jerusalem temple at risk of their lives is absurd. Why would so many endanger their lives repeatedly to propagate a lie?

Within a few weeks of the first Easter Sunday, the disciples of Jesus testified unashamedly and courageously that Jesus who was crucified rose from the dead and visited them. They told how the resurrected Jesus explained to them the scriptures, that the Messiah must suffer and die, and on the third day be raised. The disciples shared how the risen Lord had comforted them, had promised to be with them always, and had sent them on a mission to tell the world it is forgiven.

I can think of no more convincing explanation for the sudden, almost immediate resuscitation of what was an otherwise completely crushed campaign, than the one the disciples gave. I can think of only one thing that could explain their dramatic transformation from silent, scattered, terrified fugitives to fearless, unified, public proclaimers. I’m not talking about a conspiracy to lie. Obviously I’m talking about the actual resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

Could they have made the whole thing up? Yes. Could they have been spreading their lie for attention, to cause trouble, or for a scam? Yes. Do I think that they were in a state of mind to do this, and do I think they’d take beatings, imprisonment, and even death for a story they supposedly made up? Not in the least.

Parenthetically, note that the disciples left intact this terrible account about themselves for the public record. There appears to have been no cover-up. They couldn’t have come off looking worse if they’d tried. The Gospels include the good, the bad, and the ugly. There’s no spinning the disciples’ behavior in a favorable light. On the contrary, the Gospels give you the disciples as they are—warts and all. Such honesty lends itself to credibility.

Also, parenthetically, the Gospels don’t let you idolize the disciples as sterling champions of faith. They failed miserably, the Gospels insist. No hero worship allowed. Unless . . . unless your idea of a hero is one who allowed his failed life to be redeemed by a power beyond his ability and control.

6. All gospel accounts of the resurrection attest to an empty tomb and a missing body, facts that were never disputed or disproved. This may sound obvious, but it shouldn’t be overlooked. Here it is in all four Gospels:

- Matthew 28:5-6 But the angel said to the women, "Do not be afraid; I know that you are looking for Jesus who was crucified. 6 He is not here; for he has been raised, as he said. Come, see the place where he lay.

- Mark 16:5-6 As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man, dressed in a white robe, sitting on the right side; and they were alarmed. 6 But he said to them, "Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him.

- Luke 24:2-5 They found the stone rolled away from the tomb, 3 but when they went in, they did not find the body. 4 While they were perplexed about this, suddenly two men in dazzling clothes stood beside them. 5 The women were terrified and bowed their faces to the ground, but the men said to them, "Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here, but has risen.

- John 20:1-2 Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene came to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the tomb. 2 So she ran and went to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved, and said to them, "They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him."

Even those who believe that the disciples stole Jesus’ body to fake his resurrection do not deny that the tomb was empty and the body was gone. On the contrary, if the body is missing—whatever the reason—, then the tomb is necessarily still empty.

The only way to argue that the tomb was not empty is to produce the body of Jesus. And no one ever did; nor did anyone ever make such a claim. If that had been done, that would be proof positive that he didn’t rise. If you can produce his body, then there is neither an empty tomb nor a risen Jesus. Yet no such claim is a part of the historical record, biblical or otherwise. No one ever disputed the empty tomb or the missing body. This is strong evidence that there was an empty tomb and the body was gone.

The Jewish Talmud arguably makes a few unflattering references to Jesus including the accusation that he was the illegitimate son of a loose woman and a soldier named Panthera (or Pantera, or Pandera). An early Christian writer corroborates this. “According to Origen, Celsus wrote:

“ . . . when she (supposedly Mary) was pregnant she was turned out of doors by the carpenter (supposedly Joseph) to whom she had been betrothed, as having been guilty of adultery, and that she bore a child to a certain soldier named Panthera.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiberius_Iulius_Abdes_Pantera

Some speculate that the burial monument (pictured ) in Bad Kreuznach, Germany remembers Jesus’ “real” father, linking him to the man referred to by the Talmud, Origen, and Celsus. Tiberius Iulius Abdes Pantera (c. 22 B.C. – A.D. 40) was a Roman archer. The inscription (pictured in Latin) translates:

Tiberius Iulius Abdes Pantera

from Sidon, aged 62 years

served 40 years, decorated(?) former soldier

of the first cohort of archers

lies here

This same false charge concerning Jesus’ parentage may also be found in Scripture.

- John 8:19 Then they said to him, “Where is your Father?”

- John 8:41 "We are not illegitimate children."

The implication of Jesus’ opponents, it seems to me, is that: We know who our father is, but you don’t. We’re legitimate sons, but you aren’t.

All the insults aside, it is a fact that no Talmudic writings ever disputed the empty tomb or the missing body; neither did Roman historians; and neither did even Jesus’ enemies in the biblical record.

Yes, Jesus’ resurrection was denied. Yes, the disciples are accused of stealing the body to fake a resurrection. Yes, Jesus and his followers are maligned in these ancient sources. Yet no one disputed the empty tomb and the missing body. If they could have, they would have. This is not proof positive of the resurrection of Jesus, but it is a piece of evidence that should not be ignored. No one ever produced the body. No one ever denied that the tomb was empty. No one ever denied that the body was gone.

7. That the resurrection was the center of the New Testament’s Christian preaching is a strong argument for the historicity of the resurrection of Jesus. Rather than focusing on Jesus’ message of life abundant in the kingdom of heaven, something dramatic must have happened to make the earliest Christian’s central message shift to Jesus himself, specifically to his death and resurrection. They could have tried to hold his kingdom preaching at the center as one might logically expect. Life in the present and coming kingdom of heaven was the core of Jesus’ message, and so it follows that for the first Christians it would have been the same. But instead they (including and especially the Apostle Paul) began to emphasize “Jesus crucified and risen” as the core message. His crucifixion and resurrection took on central importance over anything Jesus said.

Here is a quote from the Apostle Paul that I think is one of the best passages in the Bible. It’s clear and unequivocal. It’s as bold and forceful and risky as anything written therein. Listen to Paul as he explains the unsurpassed importance of Jesus’ historical resurrection from the dead:

- 1 Corinthians 15:12-19 Now if Christ is proclaimed as raised from the dead, how can some of you say there is no resurrection of the dead? 13 If there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ has not been raised; 14 and if Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain. 15 We are even found to be misrepresenting God, because we testified of God that he raised Christ -- whom he did not raise if it is true that the dead are not raised. 16 For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. 17 If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. 18 Then those also who have died in Christ have perished. 19 If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied.

I agree with Zeitlin and most modern scholars that Christianity emerged not so much from the teachings of Jesus as from faith in his resurrection. (p. 164) Seeing with his own eyes Jesus risen from the dead sealed the message for Paul and for those to whom he appeared. Knowing that Jesus promised humanity a resurrection on the last day became credible because those first disciples saw him risen and alive. They experienced his resurrection as proof and promise of their own.

This emphasis on the resurrection of Jesus isn’t, to my way of thinking, obsession with signs and wonders. It wasn’t so much the miracle itself that became central to Christian preaching, but what the resurrection meant. The resurrection pointed to who Jesus was:

- John 11:25 Jesus said to her, “I am the resurrection and the life."

His resurrection to life is a revelation of his identity as the resurrection and the life.

So that is why even today the resurrection of Jesus is more central to Christian preaching than Jesus’ kingdom of heaven preaching. Both are essential. But resurrection has taken center stage, and this is evidence for the historical resurrection of Jesus. It took something mighty hefty to outweigh Jesus’ sermons.

8. The very existence of the early church is evidence for the resurrection of Jesus. The first Christians were monotheistic Jews. They risked their reputations as Jews, if not their very lives, to profess their belief in Jesus’ equality with God the Father. What event could possibly cause a devout, monotheistic Jew to consider a two-person God (much less three—Father, Son, and Spirit)?

At stake was the first Christian’s belief in Jesus’ divinity. His equality with God seems to contradict the hallmark of Judaism: There is one God; God is one.

- NIV Deuteronomy 6:4 Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.

To claim that Jesus and the Father are one, to many then and now, is polytheism. (And idolatry too.) The clash with monotheistic Judaism begins with Jesus’ claims about himself recorded in the Gospels. He declared oneness with his Father, and his Jewish opponents responded violently.

- John 10:30-33 “The Father and I are one.” 31 The Jews took up stones again to stone him. 32 Jesus replied, "I have shown you many good works from the Father. For which of these are you going to stone me?" 33 The Jews answered, "It is not for a good work that we are going to stone you, but for blasphemy, because you, though only a human being, are making yourself God."

- John 8:58-59 "Very truly, I tell you, before Abraham was, I am." 59 So they picked up stones to throw at him, but Jesus hid himself and went out of the temple.

“I am” is God’s name in the Old Testament.

- Exodus 3:14 God said to Moses, . . . "Thus you shall say to the Israelites, 'I AM has sent me to you.'"

Not only was Jesus’ divinity at stake, however. His claim to divinity is linked to his claim to be Messiah (Christ). Jews of the 1st Century (and today) believed that the Messiah cannot die. Upon his death, some if not all of Jesus’ disciples gave up on their hope that he was the Messiah. Listen to what Cleopas and partner said of their fallen leader.

|

| Crushed hope |

- Luke 24:19-21 “ . . . [Jesus of Nazareth] was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, 20 and . . . our chief priests and leaders handed him over to be condemned to death and crucified him. 21 But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel."

Their hope that Jesus was the one to redeem Israel means they had believed him to be the Messiah. But Jesus’ death crushed that hope. They gave up. Why? Because the Messiah can’t die; therefore, we were mistaken; and Jesus wasn't the messiah. Hope crushed.

Of course Luke tells us that the risen Jesus explained to them that the Messiah must die and rise to life forever more. So in this sense, death did not cancel Jesus’ Messiahship. His resurrection confirmed it. It is only after Jesus’ resurrection that the disciples truly understand his eternal Messiahship because it was linked to his divinity:

- Matthew 28:9 Suddenly Jesus met them and said, "Greetings!" And they came to him, took hold of his feet, and worshiped him. (italics mine)

- Matthew 28:17 When they saw him, they worshiped him; but some (still) doubted. (italics mine)

- Luke 24:52 And they worshiped him, and returned to Jerusalem with great joy . . . (italics mine)

- John 20:27-28 Then he said to Thomas, "Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe." 28 Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!” (italics mine)

So they began to spread the message that the man Jesus rose from the dead making him both Messiah and Lord. Peter declares in a sermon recorded by Luke in Acts:

- Acts 2:36 “Therefore let the entire house of Israel know with certainty that God has made him both Lord (God the Son) and Messiah, this (man) Jesus whom you crucified."

And listen to Paul:

- Philippians 2:5-11 5 Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, 6 who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited (or grasped or clung to), 7 but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, 8 he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death -- even death on a cross. 9 Therefore God also highly exalted him (by raising him from the dead) and gave him the name that is above every name, 10 so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend (in homage or worship), in heaven and on earth and under the earth, 11 and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ (Messiah) is Lord (God the Son) to the glory of God the Father. (bold italics mine)

- Romans 1:1-4 Paul, a servant (slave) of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God, 2 which he promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy scriptures, 3 the gospel concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh (a son of man or a human being) 4 and was declared to be Son of God with power according to the spirit of holiness by resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ (Messiah) our Lord (God) . . .” (italics mine)

- Romans 14:9 For to this end Christ (Messiah) died and lived again, so that he might be Lord (God) of both the dead and the living. (italics mine)

Do you see what this means? It means that the physical resurrection of Jesus is the cornerstone to his claim to Messiahship. It also confirmed his oneness with the Father. And it confirmed his claim to be the Lord. Because of his death and resurrection, Paul claims that the man Jesus is both the Lord God and the Messiah. This is a radical message by any standard of the day (or any day).

|

Athanasius: Egyptian

bishop said by Gonzalez

to have been called by his

enemies "The Black Dwarf,"

referencing his skin color

and his diminutive height |

The Church Fathers focused a great deal on the subject of Jesus’ divinity. The Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325) devoted the lion’s share of its time, attention, and documentation to the clarification of Jesus’ nature. Their conclusion, championed by Athanasius of Alexandria, was that Jesus was both fully man and fully God. Jesus shares divinity with his Father. They are in union. This view is the mark of orthodox Christianity everywhere. And though debated since then, it remains the Christian understanding of the nature of the man Jesus who is Messiah (Christ) and God the Son.

The first leaders of the Christian movement (all Jews) made an improbable and immense shift theologically, didn’t they? And a painful shift it must have been. For Jews to see a partnership within the personages of God was an unprecedented step. Any monotheist is going to balk at something that at least on the surface challenges God’s oneness. Yet, in spite of the groundbreaking theological revolution it initiated, and in spite of the danger in believing such “blasphemy,” the first Jewish followers of Jesus stood their ground. Though they believed in and worshiped God the Father and God the Son, they did not see this as a violation of God’s oneness. On the contrary, they saw this as a full revelation of God’s true relational nature, in the image of whom human beings are created. And for that revelation many in the early church suffered and died.

At the heart of this revelation is Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. His crucifixion is the cornerstone of his exaltation, and his resurrection is the cornerstone of his divinity—both Messiahship and Lordship. The author of Revelation painted this with dazzling clarity:

- Revelation 5:11-13 Then I looked, and I heard the voice of many angels surrounding the throne and the living creatures and the elders; they numbered myriads of myriads and thousands of thousands, 12 singing with full voice, “Worthy is the Lamb that was slaughtered to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!" 13 Then I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, and all that is in them, singing, "To the one seated on the throne and to the Lamb be blessing and honor and glory and might forever and ever!"

John’s slaughtered lamb is alive and standing next to the one on the throne. (See Chapter 9 for a closer look at this scene.) This is the heavenly oneness of the crucified, risen Son and his Heavenly Father. They share all blessing and honor and glory and might forever because they are one. There are many more scriptures that insist on Jesus’ divinity and his equality and oneness with his Father, but I’ll quote two from the first chapter of John’s Gospel.

- John 1:1 & 14 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 14 And the Word became flesh and lived among us . . . (italics mine)

- John 1:18 No one has ever seen God. It is God the Son, who is close to the Father's heart, who has made him known. (emphasis mine)

There it is: Jesus is God in the flesh; Jesus is God the Son. The miracle is that the early church survived given that this was its message: The crucified one is Messiah; the resurrected one is equal with God. Neither Rome nor Judaism could stamp out this message, though both surely tried. Tacitus expressed genuine exasperation at the continuation of what he wrote off as a pernicious superstition. But the movement would not stop. Internal dissent at the Council of Nicea and beyond did not stamp out this message that the risen Messiah is one with Father God, though Arius and others surely tried. If the resurrection were a lie, I think opponents would have easily succeeded in discrediting the claim. But since they all failed and the Church and its “far-out” message survived (even thrived), the Church’s very existence argues for Jesus’ physical resurrection from the dead.

Are there those who deny Jesus’ Messiahship? Yes. Are opponents of Jesus’ equality with God numerous (both within the church and without)? Yes. Even so, the scriptural evidence is compelling. You can argue that these beliefs are ludicrous. I completely understand. But it’s not so easy to argue that Jesus’ Lordship (divinity) and Messiahship weren’t basic and essential to the first believers.

9. Why did Jesus’ first followers—all Jews—begin worshiping on Sunday rather than the Jewish Sabbath? Scripture attests to this. Almost all Christians to this day worship on Sunday. This argues for his resurrection.

The first Christians were law-abiding, Sabbath-keeping, worship-going Jews. Jews throughout the Roman world—whether Jews by birth or conversion—observed the Sabbath on Saturday. Do you think that you personally could convince a practicing Jew to celebrate the Sabbath on a different day? Think about it. What would you have to do to get a Jew to worship on, say, Sunday morning instead of Saturday morning? Ask your local rabbi to propose such a change at his next synagogue council meeting!

I’m not sure if it’s appreciated today how radically “Sabbaterian” some Jews of Jesus’ general period were. From Scripture you are probably aware of things like it being unlawful to carry your mat on the Sabbath, or pluck grain on the Sabbath, or heal (considered the practice of medicine and therefore work) on the Sabbath. But 1 Maccabees (an apocryphal Jewish record of events around 175 B.C.) gives a dramatic account of Jews guarding Sabbath regulations with deadly seriousness.

- 1 Maccabees 1:41-43 41 Then the king (Antiochus Epiphanes who sacked Jerusalem and profaned the temple) wrote to his whole kingdom that all should be one people, 42 and that all should give up their particular customs. 43 All the Gentiles accepted the command of the king. Many even from Israel gladly adopted his religion; they sacrificed to idols and profaned the sabbath.

- 1 Maccabees 2:31-38 31 And it was reported to the king's officers, and to the troops in Jerusalem the city of David, that those who had rejected the king's command had gone down to the hiding places in the wilderness. 32 Many pursued them, and overtook them; they encamped opposite them and prepared for battle against them on the sabbath day. 33 They said to them, "Enough of this! Come out and do what the king commands, and you will live." 34 But they said, "We will not come out, nor will we do what the king commands and so profane the sabbath day." 35 Then the enemy quickly attacked them. 36 But they did not answer them or hurl a stone at them or block up their hiding places, 37 for they said, "Let us all die in our innocence; heaven and earth testify for us that you are killing us unjustly." 38 So they attacked them on the sabbath, and they died, with their wives and children and livestock, to the number of a thousand persons.

Devout Jews of that period strictly observed the Sabbath, sometimes even when it meant death. The Lord our God said to rest on the seventh day of the week and keep it holy. (Exodus 20:8) The Sabbath day is set on the seventh day of the week—Saturday. (Genesis 2:2-3) Is there anything you can think of that would cause Jews to suddenly change their day of worship from Saturday to Sunday?

Though the apostles were Jews, the gospel did, thanks mainly to Paul and his assistants, make its way into the gentile world. Yet the first Christian congregations in Asia Minor and Europe who where brought to Christian faith by Paul were still populated by Jews (either by blood or conversion). Whether in Jerusalem or Corinth, the Jews who became Christians were accustomed to worshiping on the Sabbath. “Accustomed” is too weak a word. It wasn’t mere habit. It was law. Obedient worship on Friday night and Saturday were all they’d ever known. (Jews mark the beginning of the Sabbath at sunset on Friday, and the end of the Sabbath on sunset Saturday.)

But something happened. Apparently Jesus’ Jewish followers had an experience that rearranged the furniture of their minds. It was an experience so extraordinary as to convince them to worship not on their own Jewish Sabbath, but on the morning of the first day of the week, Sunday. What could make such an unthinkable thing actually happen? (You know where I’m going.)

This switch from Saturday worship to Sunday worship should not be downplayed. This shift is colossal. Sunday, the day of Jesus’ resurrection, took precedence in the early church over the obligatory Saturday Sabbath services, and has ever since. How early? Very early. Paul may be referring to Sunday worship in this verse:

- 1 Corinthians 16:2 On the first day of every week, each of you is to put aside and save whatever extra you earn, so that collections need not be taken when I come.

Sure, there may have been more pagan converts than Jews and Jewish converts in the Corinthian congregation. Who knows? From Paul’s letters to them we know that there were both. Nevertheless, the point remains. The Jews of Corinth who believed Paul’s message of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection appear to have made the monumental shift to worshiping on Sunday.

It is the scholarly consensus that Paul wrote 1 Corinthians in the 50s A.D. The author of Luke-Acts, probably writing in the 80s A.D., records a worship service held on Sunday too, but the event he writes about can be dated earlier, also in the 50s A.D.:

- Acts 20:7 On the first day of the week, when we met to break bread, Paul was holding a discussion with them; since he intended to leave the next day, he continued speaking until midnight.

“New Testament believers are not under the Old Testament Law (Rom. 6:14; Gal. 3:2425; 2 Cor. 3:7, 11, 13; Heb. 7:12),” writes author Ron Rhodes. “By His resurrection on the first day of the week (Matt. 28:1), His continued appearances on succeeding Sundays (John 20:26), and the descent of the Holy Spirit on Sunday (Acts 2:1), the early church was given the pattern of Sunday worship.” And this pattern wasn’t a later development, but a direct result of Jesus’ Sunday resurrection and the cataclysmic effect it had on the first Jewish believers.

Today, a few Christian denominations continue to worship on Saturday—Seventh Day Adventists for example. But the “eighth day of the week,” Sunday, the day of Christ’s resurrection is the Christian norm for weekly worship around the world, and has probably been the norm from the time of the apostles.

You might argue that 1 Corinthians 16:2 was a meeting, not necessarily worship. Could be. But if you try to argue that Acts 20:7 also is describing a Sunday meeting rather than a worship service, you have a problem. “Breaking bread” is alternative terminology for communion (the Lord’s Supper), a core act of Christian worship. Respected commentators F.F. Bruce and O. Cullmann agree that Acts 20:7 is the first clear reference to the practice of Sunday worship. Compare Acts 20:7 with Acts 2:42:

- Acts 2:42 They devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers.

Early Christian worship entailed teaching, fellowship, communion, and prayer.

Is there more scriptural evidence that the first Christians moved their worship service from Saturday to Sunday? I think so. Sunday worship is implicit in these two verses from the Gospel of John:

- John 20:19 When it was evening on that day, the first day of the week, and the doors of the house where the disciples had met were locked for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them and said, "Peace be with you."

- John 20:26 A week later his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were shut, Jesus came and stood among them and said, "Peace be with you."

I think John is telling us that these Sunday resurrection appearances helped establish a pattern of Sunday worship. Jesus’ resurrection took precedence over their Sabbath traditions no matter how heartfelt they were. All over the world today, for almost all Christians, the primary worship service of the week is held on Sunday. What’s your best explanation?

Parenthetically, the church has never considered Sunday to be a replacement Sabbath day. Theologically the church has tended to view Sabbath as an experience, not a specified calendar day. Additionally, the church has tended to view Jesus as the Sabbath. He is Sabbath rest.

- Matthew 11:28 “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest.”

What was Jesus’ take on the Sabbath?

- NET Mark 2:27-28 Then he said to them, "The Sabbath was made for people, not people for the Sabbath. 28 For this reason the Son of Man is lord even of the Sabbath."

- John 5:15-17 The man went away and told the Jews that it was Jesus who had made him well. 16 Therefore the Jews started persecuting Jesus, because he was doing such things on the sabbath. 17 But Jesus answered them, "My Father is still working, and I also am working.”

10. The extreme transformation noted in James and Paul is perhaps the best argument for the resurrection of Jesus.

Jesus' little brother, James, one of four of Jesus’ brothers who didn’t believe in him (John 7:5), a member of the Nazareth clan who rejected Jesus and who tried to throw him off a cliff (Luke 4:16-30), a family member who believed Jesus to be insane and tried to restrain him (Mark 3:21), was dramatically convinced by some event that occurred shortly after the crucifixion, that James’ doubtful, misguided, insane brother was actually the Messiah, the Son of the living God. (What would it take to convince you that your brother is The Lord?) His mind was completely changed, and suddenly he believed his own brother, Jesus, was worthy of being worshiped. In the New Testament Book of James, almost certainly written by Brother James, he calls his own brother “our glorious Lord Jesus Christ.” (I call him “Brother James” to distinguish him from other men named James in the New Testament) To me that’s astonishing. How can you explain this dramatic reversal, this shocking transformation?

Paul says that the risen Jesus appeared to his brother, James (1 Corinthians 15:7), but he gives no account of that encounter. Perhaps the personal appearance to Brother James suggests that their private meeting was to be kept private. Whatever it was that happened and whatever was said, it worked. James not only became a believer in his big brother, he soon became the leader of the Jerusalem church over the likes of Peter and Paul. And like Peter and Paul, who each had a private visit with the risen Lord (Luke 24:34; 1 Corinthians 15:5 & 8), the details of his conversation with Jesus are not recorded. Strange isn’t it? And I don’t think it’s a coincidence. The most important three men in the early church are Peter, Brother James, and Paul. The risen Lord appeared to all three individually, says Scripture. And the contents of Jesus’ meetings with all three are not divulged.

In support of this argument concerning James’ about face, Jesus’ mother and other brothers—Joses, Judas, and Simon (Mark 6:3)—follow Brother James in becoming believers in Jesus after the resurrection.

- Acts 1:12-14 Then they returned to Jerusalem from the mount called Olivet, which is near Jerusalem, a sabbath day's journey away. 13 When they had entered the city, they went to the room upstairs where they were staying, Peter, and John, and James (son of Zebedee), and Andrew, Philip and Thomas, Bartholomew and Matthew, James son of Alphaeus, and Simon the Zealot, and Judas son of James. 14 All these were constantly devoting themselves to prayer, together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers. (italics mine)

The Bible doesn’t say that Jesus appeared to his mother. Nor does it say that he appeared to all of his brothers (or sisters). But it does specifically say that he appeared to Brother James. Perhaps James’ report of that appearance was enough to convince the rest of the family that Jesus, the one whose sanity they doubted, was indeed “the resurrection and the life.” (John 11:25) Their change of opinion concerning Jesus supports his historical resurrection.

You might argue that James didn’t really see his risen brother. Couldn’t he have just been a religious opportunist, stepping in with a lie that he’d seen Jesus, aiming to take the helm of the church, make a name for himself, be important, and make a living? Perhaps. But let me show you what Josephus wrote about Jesus’ little brother:

- Antiquities of the Jews 20:200 [W]hen, therefore, Ananus was of this disposition, he thought he had now a proper opportunity [to exercise his authority]. Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the Sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others, [or some of his companions]; and, when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned.

Pardon my sarcasm, but I wonder if one of the perks for attaining the title “Senior Pastor of Jerusalem First Church” was stoning by the Sanhedrin.

(For more on Jesus’ family relationships and tensions see

Jesus Unplugged, Chapter 3: “He Said No to His Family.”)

Paul, a devout Jew in the party of the Pharisees, went from leading campaigns of persecution against Christians as heretics to becoming a follower of Jesus' and his primary messenger to the world outside of Judaism. His about-face parallels Brother James’.

In the community of learned Jews, Paul certainly lost face and position for his sudden embrace of Jesus, but moreover he risked his life. Read Acts 21-28, the climactic final eight chapters of the Book of Acts, and you will get a taste of how risky his allegiance to Jesus was. Paul’s life was turned upside down. What dramatic experience could account for his reversal on Christianity, his risking of his standing and reputation, his risking of his life, his enduring numerous beatings, imprisonments, shipwrecks, and his surviving an actual stoning (2 Corinthians 6:4-5; 11:21-30)? What fueled his sudden single-minded commitment to the building up of Christian churches? How do you account for his staggering statement that he considers all he ever held dear to be excrement in comparison to knowing Christ (Philippians 3:8)? And based on his Christian-persecuting ways, how can we blame the churches for not trusting him at first? Can you blame them for being suspicious given Paul’s track record? (Acts 9:13 & 26) It took time before they believed he was sincere. But he was sincere. He enslaved himself to Jesus risking everything for that most precious pearl. (Matthew 13:45-46)

Couldn’t Paul have been faking? Couldn’t he have just been a religious opportunist, stepping in, lying about seeing Jesus to take the helm of the church’s missionary team, making a name for himself, being important, and making a living? It’s possible, though highly unlikely. What else can account for Paul’s abrupt and amazing transformation better than what he claimed?