My first job interview in the Golden State was this summer in Long Beach, and I was headed back down the Pacific Coast Highway to the couch of a friend in Oceanside. I stopped for gas in laid-back Laguna Beach, and went inside to grab a soda before going back to my Jeep.

“You’re a long way from home, man,” the dude observed.

“Yeah,” I said opening the door and leaning on it, “I moved out here in June looking for work. I’m just taking the scenic route back to Oceanside.”

“You don’t have a southern accent,” the chick complained.

“No, ma’am, not much of one. I’m originally from Atlanta. My dad was an English major. My grandmother taught English. Maybe that explains it.”

I waved and started to get in when the guy called out, “Hey, Dude!” And with arms outstretched and sporting a toothpasty grin, he said:

“Welcome to paradise!”

He had a point. Mild sunny temperatures almost all of the time. Beaches and beautiful people luxuriating in a lack of urgency. Palm trees and tropical drinks. Mountains, deserts, and marinas. Hikers, bikers, and bikinis. Sailors, skiers, and skaters. Maybe California was paradise. But for me, so far, it is paradise without a job and without a home.

Atlanta had plenty of homeless people in the mid 1980s when I last lived there, and, as I recall, churches as far away as Druid Hills began installing security systems because the homeless were moving east and found themselves wandering unaccompanied through church halls. My only contact with them was twice volunteering at a soup kitchen. There were disabled vets and single moms with kids. I did not enjoy the experience.

Homeless, transient, drifter, hobo, vagabond, vagrant, tramp. I do not know the proper words or their definitions. But as a pastor of small-town Mississippi churches near interstates, the “homeless” in my life were always passing through. Some were actually trying to get from here to there. But some were just homeless people who preferred moving to staying. Almost all of them asked for money when they called from the gas station or showed up at my door, but cash was against church policy. I bought them gas or groceries. On an inclement night, I got them a room.

When my own money ran out in Oceanside this summer, I walked up the beach two miles to the pier to worry and pray at sunset. I felt a panic I had never felt. Up on the pier, I leaned back on the railing and stared at two benches. I said to myself, Bert, you are one step away from sleeping right there, which probably was not reality, but the fear was.

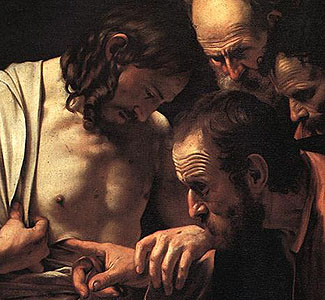

At that moment, a man my age with a backpack staked out the bench on the right. He lay down for the night, putting his head on a pillow, and pulling a blanket to his chin. It took a moment to register that his face was sending me a message from God. On his face, a face the same age as mine, was infinitely more peace than on my own. I heard Jesus say to me, Son, I am taking care of that man. I love him. And I am taking care of you too.

After that I began seeing homeless people everywhere. And I gave them something every single time. The lady passing my sidewalk table at the coffee shop. The skinny guy on the bank steps. The old guy with a sign at the traffic light. The young woman with two daughters sitting on the curb at the gas station. The brash punk with the shakes at the marina. The drunk with one shoe who sleeps in a doorway. I gave because I had to. I absolutely had no choice. If I had not given, my heart would have gone cold and died. I had become somehow connected to the homeless in paradise.

I got a check for some writing I did for Plain Truth Ministries, and my folks sent a check, so I thanked my buddy in Oceanside for putting me up, and I got an efficiency in Arcadia. My daily walk on Oceanside beach turned into a daily jog in Arcadia County Park near the famous Santa Anita Racetrack at the foot of Mt. Wilson. The homeless there found me, but I did not see them at first.

I suspect he had been there all along, but the park is not tiny, over a mile around. I finally took note of a little white-bearded guy. He was sleeping during the day in a tiny army-green tent next to a cart covered with black plastic, all but invisible in the deep shade of a huge park tree. Then I began to see others. The scattering of people who lay in the grass? They were not sunbathers or picnickers or joggers cooling down. Homeless people slept there by day, and they slept alone. Arcadia County Park is a bedroom community.

I suspect he had been there all along, but the park is not tiny, over a mile around. I finally took note of a little white-bearded guy. He was sleeping during the day in a tiny army-green tent next to a cart covered with black plastic, all but invisible in the deep shade of a huge park tree. Then I began to see others. The scattering of people who lay in the grass? They were not sunbathers or picnickers or joggers cooling down. Homeless people slept there by day, and they slept alone. Arcadia County Park is a bedroom community.

At sunset, however, the sleepers awake and congregate. Lone dreamers by day, they gather by night at picnic tables, under pavilions, and on steps to brag, laugh, argue, drink, and smoke until the morning light separates them again.

I met a Chinese nurse in the park who told me that when the homeless end up in the emergency room, she is required to send them to a shelter, but they rarely go. The evening weather is too gentle and the midnight company too sweet to waste indoors.

I am a homeless guy, in a way. My dad was an itinerant Methodist preacher, so we moved from parsonage to parsonage. Union City, Atlanta, Oxford, Athens, Cartersville, Decatur, Oxford again, Decatur again, Oxford a third time, and back to Atlanta. Then I joined the ranks of wandering theologians in Mississippi. Newton, Maben, Magee, Jackson, Flora, Florence, and New Hebron. Then with the nest empty and a marriage over, I took my homeless heart to paradise to heal, and hopefully work and write. After four months, I still have no job, I only have a one-room apartment, but I am writing. And healing.

Moving makes you cry, does it not? You go through old photos. Packing and hauling boxes to the truck is bad for the back and the soul. Driving away is the worst. It is like turning your back on a friend. I read somewhere about top stressors: a move, unemployment, a divorce. I have them all at the same time in paradise.

When I find a job, I will get my own place, but whether it will be in California, I do not know. I am now finally OK with that. California or not, I have a dream of taking my furniture out of storage, moving it in and arranging it, and sitting in my own leather recliner. I dream of hanging some pictures. I want to shelve some books. I want a job of meaningful service. I want to be a good father, son, brother, and friend. I thirst for it. I yearn for home.

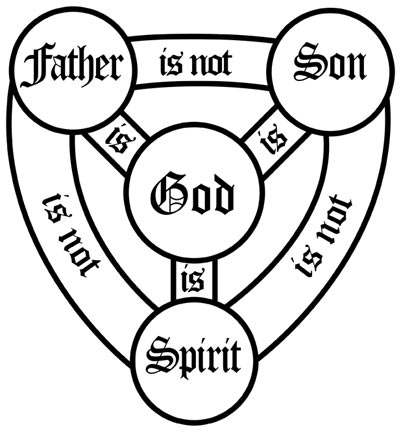

The Bible talks a lot about our abode being in God. It talks a lot about abiding in him. What this abode and abiding means, I think, is that our only real home is in him. And in the Scriptures, our abiding in him is fundamentally and finally rooted in the “incarnation” of God—God become one of us.

We did not make the move. He made the move. The incarnation means that God packed and moved. He made his home with us. So that we humans could forever be at home in God, God chose in Jesus Christ to be forever human.

God perfectly and humbly united with humanity in actual human flesh. Imagine! God packed up everything that God is and moved into our skin. The pre-existent, non-corporeal Word of God was pleased to dwell/abide with us bodily. God became an itinerant preacher with dusty sandals, a man with no place to lay his head. He laid aside equality with the Father and emptied himself taking the form of a human servant. Do you understand what that means?

It means that God was raised in a small, isolated, mountaintop village that, at around the age of thirty, he chose to leave. It means that when he returned there, they rejected him and some tried to stone him. It means that his mother and brothers were so concerned about his behavior in Capernaum that they traveled there to restrain him, fearing he had gone insane. It means God had to deal with homelessness too!

Jesus, however, spoke of a home that transcended geography. He spoke of a home in his Father and his Father’s will. And he said that we have a home in him and his Father too. “Who are my mother and brothers?” he asked. And he answered, “Those who do the will of my heavenly Father.” And what is his will? To love one another as he loves us.

We all yearn for home in a place that is larger than a brick and mortar house, and larger than a plot of land, and larger than any town, city, state, or country. Behind my yearning to be intimately beloved by someone, behind my yearning for abiding friendships, behind my yearning for meaningful work, behind my yearning for experience and adventure, behind my yearning for life full and rich and abundant, is my yearning for home in Jesus’ love.

The intimacy of conversation with him and his healing touch deep within me is everything. No other person, place, or thing will do. If I have become certain of anything on my California journey, it is that intimate union with him drives all my other passions, while also keeping all my other passions in their proper perspective. All loves that I might put before love of him are the prison of idolatry and the fire of Gehenna. And to expect of someone else or something else or someplace else to provide what I can only get from him is to find disappointment and even damage. To be without him would be the worst homelessness of all.

Maybe that is why I have developed a heart for the homeless, especially here in paradise. It is because of the spiritual homelessness that I believe we all feel, if we are honest. My heart aches for those who, just down the street from me tonight, are guarding everything they own in a bag or buggie, and who are huddling for safety and companionship in the park in which I will have the luxury tomorrow to jog. Lord, bless them and keep them all tonight.

I realize no one wants to really end up in circumstances like that. Yet, how many millions of people are today in those exact circumstances? My last blog was about homelessness, and they first come to mind when I think of people managing the margins of insignificance.

I realize no one wants to really end up in circumstances like that. Yet, how many millions of people are today in those exact circumstances? My last blog was about homelessness, and they first come to mind when I think of people managing the margins of insignificance. I once participated in a men’s event about personal significance. It was a religious program that focused on your death. I am not kidding! Apparently it is all about your epitaph. The macho speakers presented a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps approach to “men’s Christian spirituality,” one aimed at redoubling your effort to be “a good man,” so that your family, friends, church, and community will say good things about you at a ceremony while you lie dead in a casket. A well-meaning program perhaps, but also horribly misguided.

I once participated in a men’s event about personal significance. It was a religious program that focused on your death. I am not kidding! Apparently it is all about your epitaph. The macho speakers presented a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps approach to “men’s Christian spirituality,” one aimed at redoubling your effort to be “a good man,” so that your family, friends, church, and community will say good things about you at a ceremony while you lie dead in a casket. A well-meaning program perhaps, but also horribly misguided.